The MacIain People

When Iain Sprangach MacDonald took control of his lands, the people he is likely to have found there would have been a mixed lot. Some would have been descended from the Gaelic-Norse population which had been resident for hundreds of years, and some would have come in during the time of the MacDougals; and then Iain would have brought his own people.

There is no detail of how the MacIain people lived because there are few records from that time, but we can make some sensible inferences from later records. The MacIain laird is likely to have lived at Mingary Castle, though he would also have moved around his lands, staying with his people, and he would have travelled further afield. Recent archaeological evidence from the castle shows that there was a mediaeval hall built on the inside of the north curtain wall. It was built of stone, had at least two storeys, and included a chapel which was built inside the north curtain wall.

A small number of the laird’s retainers would have lived with him in the castle, but most would have stayed in the small village just to the west of the castle, on the site which is now occupied by Mingary House. From a map dating to the time just before it was destroyed in the early 19th century, we know that the village was called Mingary.

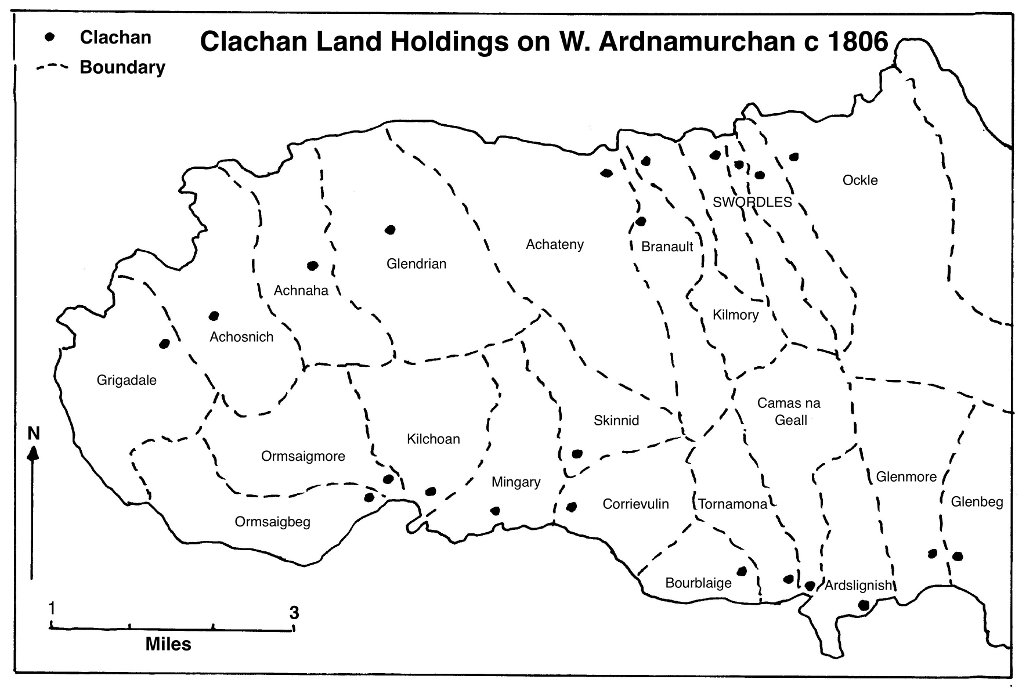

The rest of the clan lived in small villages scattered around the peninsula. These settlements are sometimes called ‘clachans’. Maps and archaeological evidence suggest that most consisted of a small number of houses built close together and sited on poor land which was surrounded by good arable land, the ‘inbye’. The way the inbye was used may have varied, but usually it was held in common, with some sort of system for distributing the fields between the resident families. Historical evidence suggests that, in some systems, the fields were drawn by lot so that every family had an equal chance of access to the best fields.

The fields were small and, often, irregularly shaped to make use of the thickest soil. They were cultivated using a ridge and furrow system, with the crops grown along the ridge and the furrow acting as drainage. The system leaves a very distinct pattern on the land which is still visible.

The peninsula was divided so that each clachan also had exclusive access to a large area of rough grazing. While animals may have been kept on this all year, the most valuable, such as the milking cows, were taken away from the village during the summer, possibly by the women and children, to remote ‘shielings’ while the men worked the inbye fields. These temporary camps are still visible on Ardnamurchan’s landscape, each little hut being marked by a circle of stones, typically 3 – 4m in diameter.

Most Ardnamurchan clachans are beside the sea. Not only did this provide an important food resource – fish – but also seaweed, a marvellous natural fertilizer which was spread on the clachan’s fields.

We do not know how Ardnamurchan was divided between settlements in the MacIains’ time, but we do have a very good map, drawn by Alexander Bald in 1806, just before the clearances, which shows the divisions at that time. While the boundaries may have changed, we know that some of the clachans date back to MacIain times as they are mentioned in what few records exist.

One clachan we know existed in MacIain times is Glendrian. Sited in the middle of western Ardnamurchan, in a great bowl in the hills, it was reorganised into the crofting system before finally being abandoned. The reference, in the Register of the Privy Council XII, 1619-1622, fol. 95b dated 3 June 1619, is to an Allester McEan Voir VcEan in ‘Glendreane’ as one of the MacIains involved in depredations against Donald Campbell of Barbreck and besieging Mingary Castle. Glendrian is now an historic monument.

Each clachan paid annual taxes to the clan chief, mostly in the form of agricultural produce. In return it was his duty to protect the inhabitants. The men of each clachan were also expected to respond when he called them to arms, and in this they were led by a man, often closely related to the chief, who is referred to as tacksman (Fear-Taic).

When the MacIains were finally driven from their lands, it’s unlikely that all the people would have fled with them, so the blood of the MacIains probably still runs in the veins of the crofters who work Ardnamurchan’s land today.